Tuesday, March 5, 2013

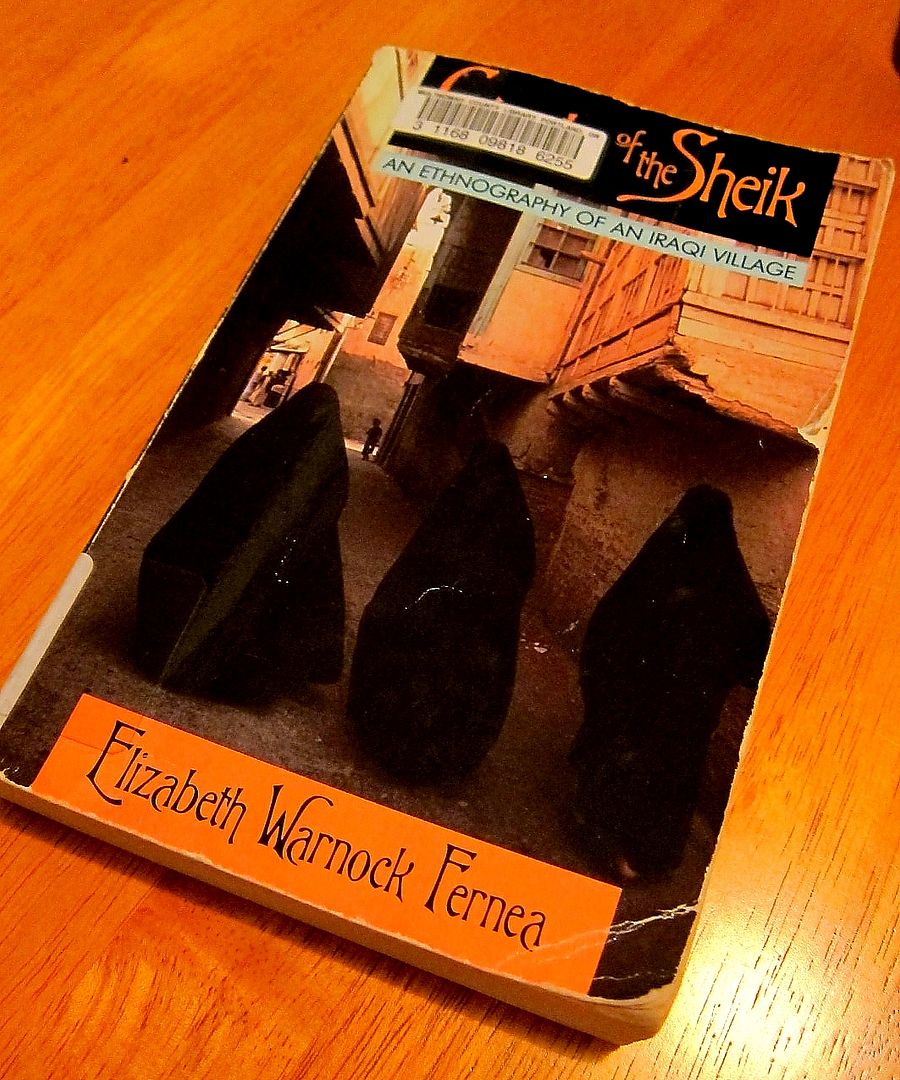

Guests of the Sheik

Lately I've been on kind of an ethnographic binge. Perhaps this is because I just finished my degree, and now I'm wondering what to do with all my free time (yeah right). Actually, I did recently complete an ethnography on Iran for my final course, and in doing so I gained such an appreciation for ethnographies and ethnographers.

I was hoping to find some good reading material this winter, and Amazon kindly guided me to "Guests of the Sheik: An ethnography of an Iraqi village." I'm sure the only reason this book came up in my search engine was because it had the word "ethnography" in the title. I wasn't particularly looking for books on Iraq, but this one caught my eye because it was written by a woman, about women.

After not buying it on Amazon, and instead checking it out from the local library, I was shocked to find that it had been published in 1969, but written about her journey which took place in 1958. 1958! Here I was thinking I was going to get a recent look at Iraqi women and the present issues facing them, but this book was written over 50 years ago. I was so disappointed that I planned on returning it, but since I didn't feel like making another trip to the library, I decided to give it a chance and read the first chapter.

The book captivated me from the first few pages. Elizabeth "Beeja" Warnock, is a newly-wed, who will has joined her anthropologist husband Robert "Bob" Fernea on his two-year field research in the remote Iraqi village of El Nahra. Before I knew it, I was a quarter into the book, and Elizabeth was baking western bread for her Iraqi neighbors, and watching as they spit it out on the floor and laughed about how awful it was. "When Bob came home he told me to forget the whole incident, to remember that we were in El Nahra to do some specific work, not prove any romantic theories about humanity being the same everywhere." (77)

That's when I knew I was in for a treat. I went into this book thinking that it would be some shallow criticism of Iraqi culture, written by an upper-middle class white women who didn't belong there in the first place. I was all but ignorant of the fact that Elizabeth Warnock is a totally famous researcher, well-informed, and a strong advocate of women's rights in West Asia. She is also, as I came to realize, a captivating writer. I would describe her in the way Henry Miller did of a fellow traveler: "when she talked about her wanderings she seemed to paint them: everything she described remained in my head like finished canvases by a master." (The Colossus of Maroussi, 1941).

From the last chapter of the book, this image remains in my mind:

"I stood with my back to the men, gazing out at the long, flat brown landscape, cut into tiny squares by the canal banks, the enormous sky dwarfing it and yet protecting it as well. The winds care from the desert and blew away the spring, but some sank into the canal and was thrown up again against the slit in the fall. The sun burned the earth till it cracked, but the winter rains filled it until it could live again. Every fall the fellahim planted grain in the square plots, and the Euphrates River water, pipped into these small canals, watered the grain and the people lived for another season. Thus it had been for more than five thousand years." (326)

But what I like the most about Warnock is her humility. Even after learning to speak fluent Arabic, living amongst the women for over a year, and making a pilgrimage to Karbala with them, she still admits to understanding very little about their culture:

"How little I really knew about the society in which I was living! During the year I had made friends, I had listened and talked and learned, I thought, a great deal, but the pattern of custom and tradition which governed the lives of my friends was far more subtle and complex than I had imagined." (266).

Even though she published this book over 50 years ago, her stories are still so relevant to the understanding of modern Iraqi culture. An internal dialogue she had with herself at a night club in Baghdad mirrors ones that I have had with myself, when caught between two cultures:

"I could tell my friends in American again and again that the veiling and seclusion of Eastern women did not mean necessarily that they were forced against their will to live lives of submission and near-serfdom. I could tell Haji again and again that the low-cut gowns and brandished freedom of Western women did not necessarily mean that these women were promiscuous and cared nothing for home and family. Neither would have understood, for each group, in its turn, was bound by custom and background to misinterpret appearances in its own way." (313)

As an International Studies major, I feel that this book should be required reading for all college students, especially hopeful anthropologists and ethnographers like myself. In the U.S. we are brought up to believe that we live better than most people in the world, and that everyone should be envious of us because of our material wealth, freedom, and mobility. This was true of Warnock's generation and ti is true of mine. However, Warnock's experience in Iraq reveals just the opposite. When we try to view the world from the lens of another culture, we find that happiness and success is measured in a very different way. "They never envied me," Warnock realized, "only made me fit, as well as I was able, into their patterns." (326)

She summarizes her main point boldly in the closing statements of her book:

"[They] pitied me, college-educated, adequately dressed and fed, free to vote and to travel, happily married to a husband of my own choice who was also a friend and companion....No mother, no children, no long hair, thin as a rail, can't cook rice, and not even any gold! What a sad specimen I must have seemed to them." (316)

I would recommend this book to anyone who is trying to shake themselves of an ethnocentric view of the world, for anyone who wants to briefly step out of their comfort zone and learn about a group of people living in an entirely different way. This book did not make me want to experience what Warnock experienced in the El Nahra, but what it left em with was a great appreciation and understanding of the people in this part of the world.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Gingham Weather

Been really enjoying my new collection of Gingham dresses from designer April Meets October. Perfect for Portland summer weather. I know own...

-

Although it's not McDonald's, Max Burger in Stockholm far exceeded my expectations for local fast food.On their website Max Burger ...

-

my mehndi hand with Iced coffee and fries For better or worse, I ended up eating McDonald's in Pakistan three times. Yes, thre...

No comments:

Post a Comment